The Houston Astros have built a successful yet complicated legacy over the last decade. The 2022 World Series is another chapter in a book filled with plot twists galore.

Since the beginning of divisional play in 1969, only the Atlanta Braves of the 1990s advanced to more consecutive league championship series (eight, 1991-99) than these Houston Astros, now with a string of six.

In reaching their fourth World Series in six years, the Astros are the first club to have such a stretch since the 1998-2003 New York Yankees teams that appeared in five World Series.

Of course, no club this good had its legacy tarnished so significantly since, arguably, the 1919 Chicago White Sox.

The Astros’ sign-stealing campaign from the 2019 season cost general manager Jeffrey Luhnow and manager A.J. Hinch their jobs. It cost the club its reputation among baseball fans outside Houston. A cloud still hangs over the franchise’s accomplishments. It may never lift.

A handful of players have been there from the beginning: from the 2017 World Series winning team through the scandal to the present, notably Jose Altuve, Alex Bregman, and Yuli Gurriel. Many believe that MLB should have punished players involved in the garbage-can-banging scheme. Commissioner Rob Manfred declined to do so.

A World Series win this season over the Philadelphia Phillies in the first year of PitchCom, the electronic pitch-calling system designed to prevent sign-stealing, would allow the Astros to prove they can reach the top of the baseball world legitimately following the scandal.

As veteran sportscaster Bob Costas said: “Those who continue to say that (the scandal) explains away their success … It just doesn’t add up. These guys have been to the LCS six straight years, and they’ve gone to the World Series four out of six. And they can’t bang on trash cans anymore.”

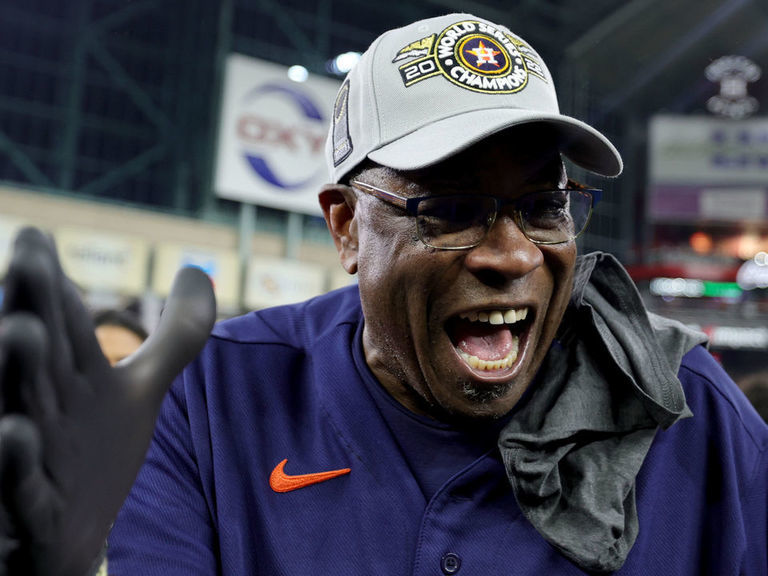

For some, nothing will completely lift the sign-stealing cloud, even if young stars such as Kyle Tucker and Yordan Alvarez and manager Dusty Baker had no role in it. But a World Series win would add some light to shine through that cloud.

Yes, the Astros were caught cheating in 2019. The organization also changed how successful teams develop players and think about skill development. They popularized tanking and cut the number of scouts and minor-league affiliates following the 2017 season. They stripped some human elements from the game. The organization helped create new opportunities for coaches and supported scores of players to reach their potential. Houston’s legacy? It’s complicated. And it could become even more complex.

Whatever anyone thinks of the Astros, there’s no doubt they’ve been influential.

Just as the “Moneyball” A’s applied data-based processes to player evaluation, one can argue that no MLB team did more to bring such an empirical-based approach to player development than the Astros.

It didn’t just work in Houston. It’s working elsewhere around the majors, most notably in Baltimore.

This summer, I asked Orioles GM Mike Elias, a former Astros executive with a dozen former Houston employees currently working for him, if he felt Baltimore’s success this year validated some of the Astros’ success. Many Houston front-office staffers have proliferated throughout the game, but they’re most concentrated in Baltimore.

“The work in scouting and player development was so exemplary and productive for that entire decade,” Elias said of his experience in Houston. “We stand by it.”

That had nothing to do with banging on trash cans.

And this season, the Orioles had one of the greatest turnarounds in MLB history.

The Astros helped Justin Verlander find a fountain of youth after acquiring him in 2017 from Detroit. The club was the first wide-scale adopter of high-speed cameras and used those images and pitch-data feedback to refine Verlander’s pitch mix. The high-tech cameras offer the ability to see exactly how a pitcher’s grip and fingertips impart spin to the ball at release, and it’s all in high def. Spin rate and spin axis govern the ball’s movement. They were details that hadn’t been explored before.

The Astros installed 75 high-speed cameras in ballparks and bullpens throughout the organization by the end of 2018. This was before most clubs had even begun experimenting with their first such device.

In Verlander’s last three healthy seasons, he produced at least 6.0 WAR per campaign – a stretch he hadn’t accomplished since his mid-to-late 20s. He’ll start Game 1 of the World Series coming off a remarkable age-39 season that has him as the favorite to win his third Cy Young Award.

The Astros have been early adopters of other methods and technology, from bat sensors to weighted-ball programs. Trial and error was a regular part of Houston’s process. The club led the American League in pitching wins above replacement and ERA this year. Since 2017, the Astros rank second to only the Los Angeles Dodgers in pitching WAR. However, they’ve done it while spending $40 million less than the Dodgers on pitching over the last three seasons.

The Astros also focused on individualized development over a one-size-fits-all approach. That’s become a more standard procedure throughout MLB.

The Pittsburgh Pirates made Gerrit Cole the No. 1 overall pick in the 2011 draft. By the end of 2017, he was a league-average arm as he adhered to Pittsburgh’s organizational philosophy of throwing sinkers down in the zone as the primary foundation of every pitcher’s arsenal.

When the Astros traded for Cole the following winter, they thought they had found ways to unlock his gifts. When spring training began, they sat Cole down in a conference room and presented him with a road map that included video and data visualizations of his strengths and weaknesses. The club planned to have him lean on his upper 90s four-seam fastball and throw his curveball more often.

“I’d never experienced any meeting like that, at all,” Cole told me in 2018. “They highlighted the fact that my curveball’s my best pitch for me, which took six years for someone to finally tell me … I was pulling out the wrong tools.”

After two All-Star seasons with the Astros in which he finished in the top five in Cy Young voting both years, Cole cashed in on his development with a $324-million deal with the New York Yankees.

Closer Ryan Pressly is another player who benefited from a similar presentation and pitch-mix change after Houston acquired him from the Minnesota Twins.

This Astros staff has homegrown development success stories like Framber Valdez, who signed for $10,000 in 2015 as an international free agent, and Cristian Javier, who also signed in 2015. They combined for 7.8 WAR this campaign. They’ve also combined for 19 1/3 innings in the postseason and allowed only three earned runs.

Like the “Moneyball” A’s helped change who worked in baseball front offices, the Astros played a role in changing who coached in professional baseball. You didn’t have to be an ex-big leaguer to land a coaching job.

St. Louis hitting coordinator Russ Steinhorn entered pro baseball through an unlikely path in Houston.

In spring 2012, he was the hitting coach at Delaware State, a tiny Division I program, when the Hornets had such an unusually successful year that their accomplishments made their way into the “Faces in the Crowd” section of Sports Illustrated in May 2012.

From the issue:

It’s no fluke that they lead the nation in this scrappiest of statistics. Coach J.P. Blandin, with the help of new hitting coach Russ Steinhorn, set out to instill a “get on base at any cost” mentality this year. “We’re not teaching them to lean out in front of pitches; we’re just teaching them not to get out of the way,” Blandin says. The Hornets have been hit more than twice as many times as they were last season, and that helped them earn a team OBP of .423 – second in D-I – and their best winning percentage (.690) since Blandin took over the program in 2001.

Sig Mejdal, then Houston’s director of decision sciences and now an assistant GM with the Orioles, read the item and was intrigued. He left a voicemail for Steinhorn.

The Astros wondered, what if you could better teach on-base skills? Those skills were considered rigid. Steinhorn soon joined them as a minor-league instructor working with a number of players on this year’s World Series roster.

The Cleveland Guardians were lauded for their league-leading 18.1% strikeout rate this year. But the Astros (18.8%) are the only team below 20% in aggregate for the last six seasons, an era when strikeout rates are generally increasing. Houston also led baseball in slugging during that period (.452).

This season, the first in the PitchCom era, the Astros posted the second-lowest strikeout rate in the majors (19.5%) and the fifth-best slugging mark (.424).

Steinhorn noted how Alex Bregman, a former No. 2 overall pick, and Chas McCormick, a 21st-rounder from a small Division II program, have been in the same playoff lineups. They benefited from the same development processes. He said it’s evidence of an organizational philosophy where players were treated equally “and provided with the same opportunities.”

What’s the Astros’ legacy in terms of player development?

“The culture of innovation and being deliberate with their process of each player – from the day they signed – was expected,” Steinhorn told theScore. “Also, how they prepared and trained had a meaning and was measured constantly by various tools that provide immediate feedback for everyone to track the direction and trends of each player’s development.”

The talent pipeline likely won’t run forever. Houston has fallen off in various farm-system rankings. Other organizations have widely adopted similar methods. And former Astros personnel are scattered throughout the game. But those processes formed in the mid-2010s are still helping this roster.

But there are other negative legacies beyond the sign-stealing scandal.

Despite its successes, Astros management made serious missteps too. There was the 2018 deadline trade for Roberto Osuna, who no other club would touch because of a pending domestic violence charge in Toronto. Osuna has pitched in Mexico and Japan over the last two years. While some Astros officials were unhappy with the trade, a year later, assistant general manager Brandon Taubman taunted a group of female reporters during the ALCS celebration by yelling, “Thank God we got Osuna! I’m so f—-ing glad we got Osuna!” He was later fired and placed on MLB’s ineligible list.

In his sign-stealing investigation of the Astros, Manfred criticized the “insular” culture of the club’s baseball operations department, saying it placed too much weight on “results over other considerations.”

Osuna, Taubman, Luhnow, and many others are all gone. PitchCom is here. The current regime has increased the number of minor-league affiliates to eight. For some, though, the cloud remains, especially regarding the sign-stealing scandal.

Fans in Houston believe this team ought to be judged on its own merits. In PitchCom’s first year, the Astros won 106 games and finished second in run differential in the AL.

Perhaps the lesson is this: as difficult as it was to turn the Disastros, a team of three straight 100-loss seasons, into these Astros, it took one cheating scheme of unknown effectiveness to damage their entire reputation. That’s a difficult thing to repair.

The Astros’ legacy? It’s complicated.

Travis Sawchik is theScore’s senior baseball writer.